Despite expectations for growth, only a few weeds have sprouted in the Milltown Dam sediments near Opportunity, where John Brown, Anaconda Superfund site project officer for the state Department of Environmental Quality, stands Thursday morning. Photo by LINDA THOMPSON/Missoulian

Dust rolls across the Milltown sediment deposits Thursday afternoon. Officials monitor dust levels at the site and attribute most of the dust to nearby haul roads that separate the ponds. Guess where the dust is going.. You guessed it, Opportunity. Photo by LINDA THOMPSON/Missoulian

OPPORTUNITY – Milltown Reservoir’s exiled dirt won’t behave in its new home.

The 2.5 million cubic yards of fine-grained sediment dredged from the former reservoir east of Missoula has been spread 2 feet thick over more than 600 acres of wasteland between Anaconda and its satellite community of Opportunity. But it won’t grow grass.

“This would have been the first year we wanted to see vegetation everywhere,” said Charlie Coleman, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Anaconda site project manager. “But the vegetation never took off.”

That’s more and less of a problem than it sounds. Less, because the Milltown sediment doesn’t appear to be posing a human health hazard. It’s sticking where it belongs on top of historic smelter wastes, and doesn’t appear to contribute to the dust clouds that occasionally stampede across the Deer Lodge Valley.

While also contaminated with poisonous levels of arsenic, lead and other heavy metals, the Milltown sediments are a lesser evil in a 5,000-acre Superfund site that holds a century’s accumulation of mine and smelter wastes piled up to 50 feet deep.

Still, there is a problem, because the Milltown sediment was supposed to grow a layer of grass and cap those mining deposits. Coleman submitted the EPA’s fourth five-year review of the Anaconda Smelter National Priority List Site this month, and the Milltown project was supposed to be a completed item. It wasn’t.

*****

Interstate 90 motorists may remember seeing lines of rail cars being unloaded south of the freeway between the Warm Springs and Opportunity exits. Those cars were filled with sludge that built up behind Milltown Dam since it was built at the confluence of the Blackfoot and Clark Fork rivers in 1908.

Atlantic Richfield Co, or Arco, bore responsibility for cleaning up that legacy of mine and smelter waste. The problems stretched from the mines and smelters in Anaconda and Butte down the Clark Fork River to Milltown Dam.

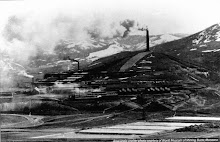

The area between the highway and Anaconda’s iconic smelter smokestack was known as Opportunity Ponds because smelter workers sluiced their waste downhill into a series of settling ponds, known as Cells A, B, C and D. The “ponds” have long since dried up, leaving behind a sprawling apron of tailings thick with cadmium, zinc, arsenic, lead and other poisons.

To fix this, Arco paid for and EPA managed years of effort to isolate the waste from surrounding ground and to cover it with a layer of safe soil and vegetation.

On the eastern edge of the wasteland, a dozen huge dump trucks and excavators were still at work last week, gathering more clean dirt to put on the tailings. The borrow pit they’ve created is nearly 1,000 acres in size, and will be converted into a prairie pothole-style wetland when they’re finished.

Elsewhere on the 5,000-acre Opportunity Ponds waste management area, clean fill over the old tailings has produced tall fields of grass. As Coleman led a tour through the site, a herd of 20 antelope grazed in one of the more established areas.

“Arco realized if this (Milltown sediment) grew vegetation, they could kill two birds with one stone,” Coleman said.

Ironically, once the Milltown excavators dug down to the level of the original riverbed, that old soil sprouted seeds that had been buried a century ago. There was hope that the excavated material, while not exactly rich potting soil, would at least support some simple field grasses.

But that didn’t happen. Most of the Milltown caps are as barren as the last exposed Anaconda tailings cell – a 20-acre plot that looks like curdled yellow cement. The only things that will grow in either spot are a few spiky thistles and tumbleweeds.

*****

Much of the sludge behind Milltown Dam got deposited there after a huge flood on the Clark Fork in 1908, which also left slickens of metal deposits along the river banks from Galen to Garrison. When Milltown Reservoir was found to be leaching arsenic into the local drinking water aquifer, EPA ordered a cleanup.

The early plans called for cleaning the gunk out of the reservoir and piling it nearby, possibly in the Bandmann Flats area between Bonner and East Missoula.

That would have been fine with Opportunity resident Serge Myers. He said many of the little community’s 750 residents feel they’ve been the janitors for everyone else’s pollution for years.

“I used to be able to see the trees at Warm Springs,” Myers said of the four-mile expanse between the two towns. Since he moved to Opportunity in 1957 as a smelter worker, the C and D cells filled in and blocked the view. When the area was declared a Superfund site in 1983, it seems the problems got bigger rather than smaller.

“I think they should all be grateful we took the brunt of it,” Myers said. “It’s nice to see the river go clean, but I thought we should at least get the property taxes from those new homes they built at Bandmann.”

Anaconda-Deer Lodge County Superfund technical adviser Jim Kuipers said dealing with one of the oldest – and largest – Superfund sites in the nation has been an exercise in patience.

“We’ve had great success downstream, with the dam removal and restoration work and new parks and trails,” Kuipers said. “Anaconda is still waiting for those things. We’re still 10 or 20 years away from being done up here.”

The Milltown grass problem shouldn’t last that long. No one’s sure why the grass won’t grow. It could be the soil chemistry is wrong, that decades of sitting under water left it too sterile to support plants. It could be a physical problem – the stuff is somewhere between a silt and a clay, which makes it tough for roots or water to penetrate.

Arco workers have set up a few test plots with added mulch, fertilizer and other additives to see if that helps. They’ve grown a few more grasses and weeds, but not enough to be successful.

“They have to make something work, or they have to go back to the drawing board,” said Chris Brick, science director for the Clark Fork Coalition, a nonprofit watchdog group monitoring the river restoration. “I don’t think we should experiment any more. They should cap it with clean soil and go on. We would advocate for getting the job done sooner than later.”